I’m going to share something with you that might just change the way you think about writing, especially if you’re like me and often find yourself needing more than a few words to get your point across. We’re talking about the haiku, a form of poetry that’s often dismissed as a simple 5-7-5 syllable exercise. But let me tell you, it’s so much more than that. This ancient Japanese form is a true master of conciseness and clarity, and for writers like us, who might be used to sprawling prose or free verse, the haiku is a unique challenge.

Imagine this: you need to distill a moment, an emotion, or an observation into seventeen syllables, spread across just three lines. And somehow, those few words need to evoke something far greater than what they literally say. That’s the art of the haiku, and I’m going to dive deep into how to master it. We’re going beyond just counting syllables to really explore what makes a simple verse resonate and leave a lasting impact.

My goal here is to unveil the layers of technique, mental frameworks, and creative approaches that help you harness the power of brevity. Mastering the haiku isn’t about limiting your expression; it’s about refining it, sharpening it, presenting it with surgical precision. It’s about understanding that every syllable carries weight, every word is a deliberate choice, and even the spaces between the words are just as vital as the words themselves. Get ready to transform your understanding of poetic economy and discover the profound beauty that comes from disciplined articulation.

Beyond the Syllable Count: The Essence of Haiku

While that 5-7-5 syllable structure is probably the most recognized thing about a haiku, it’s honestly just the skeleton, not the beating heart. True mastery comes from really grasping the underlying principles that make traditional Japanese haiku so powerful, even when we translate them into English, where trying to stick to exact syllables can sometimes mess with the meaning.

Syllable and Beat: Understanding the Kireji Connection

In Japanese, that 5-7-5 structure refers to on, or sound units. They’re not exactly like our syllables in the Western sense, but they often line up pretty closely. The real magic in those classic haiku often comes from the kireji, which they call the “cutting word.” This is like a pause or a break, usually at the end of the first or second line, that creates a little moment of suspension. It invites you, the reader, to connect two seemingly different images or ideas.

Now, in English, we don’t have direct equivalents for kireji. But we can create a similar effect by carefully placing our line breaks, using punctuation (or not using it!), and by putting images side-by-side in just the right way. That break isn’t just a breath; it’s a pivot point, allowing your mind to bridge the gap and come to a new understanding.

Here’s what you can do: Don’t just count syllables. Try to sense the beat and those natural pauses. Imagine speaking your haiku out loud. Does it flow? Does it subtly shift your perspective at the end of the first or second line?

Let me give you an example:

My original thought: The wind blows through green bamboo at night, and I hear little sounds.

My weak haiku attempt (just counting syllables):

Night wind blows through green

Bamboo makes soft rustling sounds

Quiet in the dark

But here’s a mastered version (with an implied kireji):

Wind cuts through bamboo —

Green leaves whisper secrets low,

Night holds silent breath.

Notice how “Wind cuts through bamboo —” sets up an image, and then that dash (which is like our English equivalent of a pause or kireji) shifts to a more evocative, subtle image. And then the third line brings a whole new dimension to the stillness.

Juxtaposition: The Heartbeat of Haiku

Haiku absolutely thrives on the art of juxtaposition. That means putting two or more distinct images or ideas right next to each other to create a new, often profound, meaning through their interaction. This isn’t just about making a list; it’s about creating a spark when two elements collide. The interaction should be a bit unexpected, but ultimately, it should illuminate something.

Often, one image will be really concrete and sensory, while the other might be more abstract or emotional. The reader then becomes a co-creator, bridging the gap between the two and discovering their intrinsic connection.

Here’s what you can do: Start with one strong image. Then, brainstorm a completely different image or concept that, when placed alongside the first, creates an intriguing tension or resonance.

Let me show you:

Weak juxtaposition:

Cold winter morning,

Snow blankets the silent ground,

Birds fly in the sky. (These are just three separate observations strung together.)

Effective juxtaposition:

Cold morning frost;

A child’s laughter shatters glass,

Sunlight melts the pane.

Here, the cold frost bumps up against the warmth implied by a child’s laughter, which then paradoxically “shatters glass” – a metaphorical breaking of the stillness – and then it’s all resolved by the melting sun. The images are distinct but create a powerful, evolving scene.

The Concrete and the Evocative: Sensory Details Above All

Haiku is not the place for abstract concepts or philosophical essays. It truly demands concrete imagery, appealing directly to your senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, touch. By grounding your haiku in observable reality, you give the reader a vivid, tangible experience.

Now, “concrete” doesn’t mean “boring.” The goal is to pick details that are not only sharp and clear but also evocative. A splash of water isn’t just “wet”; it might be “silvered spray” or “cold shock.” Using specific, well-chosen details lets the reader not just see, but truly feel the poem.

Here’s what you can do: When you write a line, ask yourself: Can I taste it? Smell it? Hear it? See it clearly? Feel its texture or temperature? If you can’t, swap out those generalities for specifics.

For example:

Weak sensory detail:

The sky is colorful,

Birds sing loud at sunrise now,

It feels like spring.

Strong sensory detail:

Crimson streaks light east,

Robins trill a keen sharp song,

Earth breathes warming soil.

“Crimson streaks” is so much more specific than “colorful.” “Keen sharp song” paints a more vivid picture of the sound than “sing loud.” And “Earth breathes warming soil” gives you a tactile and olfactory experience, hinting at spring without having to explicitly state it.

The Art of Omission: What Not to Say

Perhaps the greatest lesson you’ll learn from haiku is the power of leaving things out. A master haiku poet understands that silence and suggestion are just as important as the words themselves. Redundancy, explanatory phrases, and overly emotional statements? Those are the enemies of haiku clarity and impact.

Avoiding Redundancy: Every Word Earned Its Place

In a form with only seventeen syllables, every single word needs to pull its weight. There’s simply no room for filler words or phrases that just repeat or reinforce something already implied. If you can remove a word and it doesn’t diminish the meaning or impact, then it shouldn’t be there.

Here’s what you can do: After you draft something, review each line. For every single word, ask: Does this word add new meaning or essential imagery? Can I say the same thing with fewer words?

Check out this example:

Redundant:

Green leaves fall to ground,

Softly they fall in the breeze,

Autumn leaves descend slow. (These are all pretty repetitive ideas.)

Concise:

Green leaves flutter down,

A soft whisper in the breeze,

Earth sighs, autumn’s breath.

The concise version removes the repetitive “fall” and “descend slow” and replaces them with more evocative imagery that implies the movement and the season.

Suggestion and Implication: The Unspoken Narrative

Instead of flat-out telling the reader how to feel or what to think, a powerful haiku suggests. It lays out an image or a moment, inviting the reader to bring their own emotional context or narrative to it. This engagement transforms the reader from just passively receiving the poem into an active participant in its creation.

This really ties back to juxtaposition: the space between those two images is where the meaning lives, and that meaning is often what you, the reader, bring to the poem.

Here’s what you can do: Instead of stating an emotion (for example, “I feel sad”), describe a scene that evokes sadness. Instead of explaining a situation, present images that imply it.

Take a look:

Telling (no implication):

I felt so lonely

Looking out at the quiet snow,

Missing my loved one.

Suggesting (implying loneliness/loss):

Silent, falling snow —

Prints beside the garden gate

Vanished with the light.

The second haiku doesn’t say “I am lonely” or “I miss someone,” but those “vanished” footprints imply an absence and evoke a sense of quiet longing or loss, simply through clever imagery.

Eliminating Explanatory Language and Abstraction

Haiku deals with the immediate, the tangible. Phrases like “This represents…” or “It reminds me of…” or words expressing abstract concepts (“happiness,” “freedom,” “truth”) often fall flat in haiku because they just don’t have that crucial concrete grounding. Focus on showing, not telling.

Here’s what you can do: Scan your haiku for any abstract nouns or explicit interpretations. If you find them, brainstorm concrete images that embody those abstractions.

For instance:

Abstract/Explanatory:

The feeling of joy

When the spring arrives each year,

It makes me happy.

Concrete/Evocative:

Warm sun on my face,

New buds burst a vibrant green,

Robin’s quick sharp song.

The second version evokes “joy” through specific sensory details of spring’s arrival, rather than just stating the emotion directly.

Crafting Your Haiku: A Step-by-Step Approach

Let me tell you, mastering haiku isn’t about some magical inspiration arriving out of thin air. It’s a deliberate craft, a skill you build. And this structured approach I’m about to share will help you transform those fleeting observations into truly resonant poems.

Step 1: The Inciting Moment – Observe, Immerse, Feel

A strong haiku usually comes from a specific, observed moment, whether it’s in nature or your everyday life. It’s not about grand themes, but those small truths. Think about the glint of dew on a spiderweb, the sound of rain on a tin roof, the scent of fresh-cut grass, or a fleeting expression on someone’s face.

Here’s what you can do: Carry a small notebook or use your phone’s memo app. Practice “haiku hunting” – actively look for moments that really grab you. What do you see, hear, smell, touch, taste right now? What’s the feeling of this moment? Don’t overthink it; just observe.

Try this prompt: Sit by a window for five minutes. Really tune into one specific detail. A bird. A cloud. The way light hits something.

Step 2: Brainstorming Keywords and Core Images

Once you have that observed moment, capture its essence in keywords. Don’t even worry about syllables yet. Just focus on the strongest images and sensory details. What are the two or three most vital parts of this moment?

Here’s what you can do: List all the nouns, verbs, and strong adjectives that come to mind related to your inciting moment. Think about action and specific qualities.

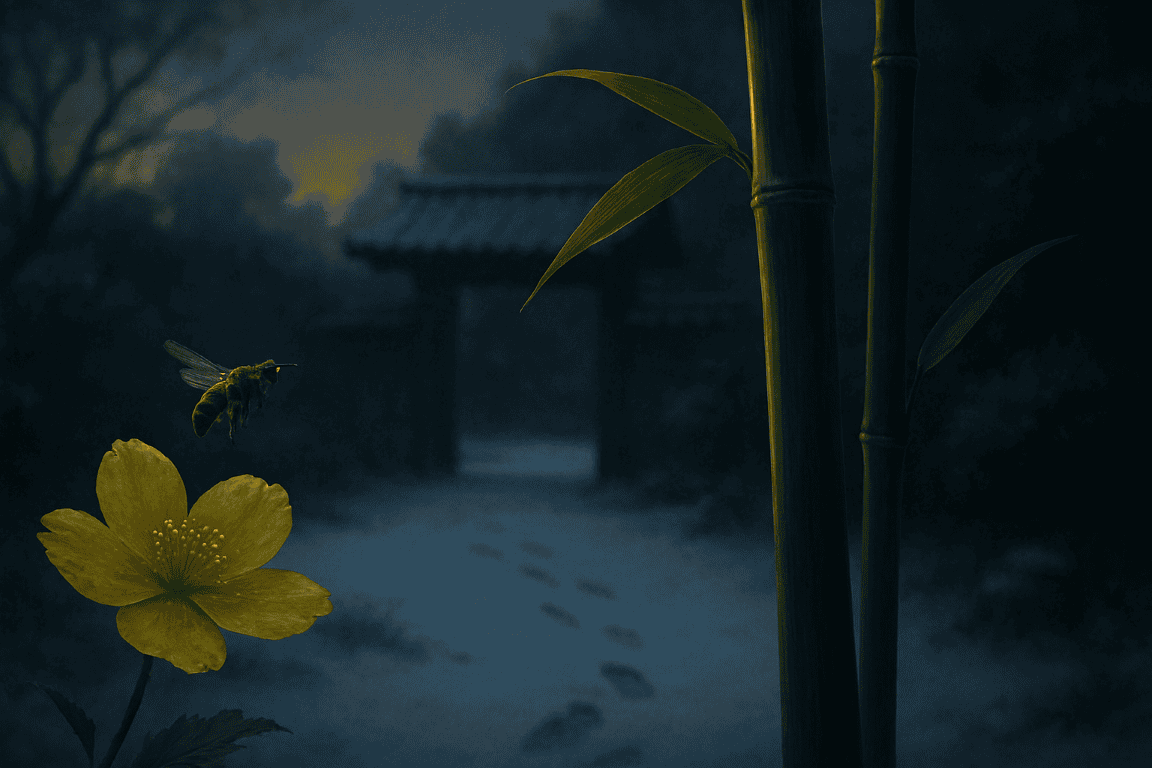

Example (based on observing a bee on a flower):

Keywords: bee, buzzing, yellow, pollen, flower, velvet, sun, warmth, low hum, sweet, leg, dust, deep, green leaf.

Step 3: Establishing the Juxtaposition – The Core Tension

Now, look at your keywords. Can you find two distinct elements that create an interesting tension or connection when you put them together? This is often where the magic really happens. Think about contrasting scale, movement, sound, or even the time of day or season.

Here’s what you can do: Look for a larger context and a very specific detail within it. Or, a static image and something dynamic. Or, even two seemingly unrelated images that, when combined, create a deeper meaning.

Example (from those bee keywords):

My initial ideas: Bee on flower (too plain). Buzzing bee, hot sun (better, but still simple).

Stronger juxtaposition: A large, vibrant flower (static, colorful) and a tiny, busy bee (dynamic, focused). What does the bee represent in contrast to the flower, or vice-versa? Is it labor versus beauty? Ephemeral life versus rooted life?

Step 4: First Draft – Flexibility with Syllables

Now, try to build your three lines. Keep that 5-7-5 structure in mind, but don’t be a slave to it just yet. Get those core images down. Be open to variations. Focus on putting those powerful words in place.

Here’s what you can do: Don’t edit heavily at this stage. Just get your words onto the page. Experiment with different verbs and adjectives.

Example (my first attempt at the bee haiku):

Yellow flower blooms. (5)

A busy bee buzzes near, carries pollen. (9 – too long)

Sun shines bright above. (5)

Step 5: The Refinement Loop – Pruning, Polishing, Perfecting

This is the most crucial stage. Here, you’re going to meticulously prune out any extra words, swap weak words for stronger ones, and make sure every single syllable counts. Read it aloud. Feel the rhythm. Check for that implied kireji.

- Syllable Count: Adjust words to fit that 5-7-5 structure. Use synonyms, or rephrase things.

- Word Choice: Are your nouns and verbs really vivid? Are there any adverbs that could be replaced by stronger verbs? Are adjectives truly necessary, or can the noun carry the weight?

- Sensory Impact: Are those images sharp and clear?

- Conciseness: Can any words be removed without losing meaning?

- Juxtaposition/Connection: Does the poem create a spark between its elements? Is there an unspoken meaning the reader can discover?

- Impact: Does that final line resonate and leave a lasting impression?

Here’s what you can do:

1. Read the haiku backward, word by word. This messes with your natural reading flow and forces you to really scrutinize each individual word.

2. Try simplifying imagery. Can a grand image be represented by one striking detail?

3. Experiment with different line breaks.

Example (refining my bee haiku):

Initial Draft:

Yellow flower blooms.

A busy bee buzzes near, carries pollen.

Sun shines bright above.

Revision 1 (focus on syllables):

Yellow flower blooms. (5)

Busy bee takes pollen now, (7)

Sun shines warm and bright. (6 – still need to adjust)

Revision 2 (focus on imagery, conciseness, and syllable count):

Velvet bloom unfolds, (5 – stronger visual for the flower)

Gold dust on the bee’s leg, (7 – more evocative than “pollen,” and specific)

Warm sun hums above. (5 – merges sound and light, implies the bee’s presence)

This back-and-forth process of drafting and refining—that’s where true mastery really comes out.

The Haiku Mindset: A Philosophy of Living and Writing

Let me tell you, mastering the haiku goes beyond just technique. It’s a whole way of looking at the world, a philosophy that informs your writing and, by extension, your entire experience.

Patience and Observation: Slowing Down

In a world that’s so saturated with information and always rushing, haiku demands that you slow down. It requires pausing, observing intently, and letting moments unfold. This patience isn’t just about finding a subject; it’s about really absorbing it, letting it resonate until its true essence becomes clear.

Here’s what you can do: Dedicate five minutes each day to simply observing, without judgment or analysis. Focus purely on sensory input. What do you notice that you typically rush past?

Embracing Limitation as Liberation

For many writers, the constraints of haiku can feel so restrictive. But a master understands that these limitations are actually liberating. The strict syllable count and line structure force your creativity, pushing you to make bold choices, to condense, to find the most potent word. This discipline truly hones your ability to write economically in any form.

Here’s what you can do: View the 5-7-5 constraint not as a cage, but as a chisel. It removes everything unnecessary, revealing the core beauty of your subject.

The Power of the Unsaid: Ma and Yugen

Traditional Japanese aesthetics offer two concepts that are profoundly relevant to haiku:

* Ma (間): This is often translated as “gap,” “pause,” or “space between.” In haiku, ma isn’t just silence; it’s pregnant with meaning. It’s that breath the reader takes between lines, the space where the two juxtaposed images collide and new understanding is formed. It’s what you implicitly invite the reader to fill.

* Yugen (幽玄): Roughly translated, this means “a profound, mysterious sense of the beauty of the universe, and the sad beauty of human suffering.” It’s not about explicit statements but about evoking a deep, difficult-to-articulate emotional response. A haiku with yugen creates a sense of awe, mystery, or poignant beauty that lingers long after the words are read.

These concepts are less about strict rules and more about the feeling a haiku conveys. A master haiku evokes yugen by subtly hinting at profound truths through precise, concrete images and the effective use of ma.

Here’s what you can do: As you refine your haiku, ask yourself: Does this poem invite the reader into a moment of contemplation? Does it suggest something larger than its literal words? Is there space for the reader’s own interpretation and emotional connection?

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Even experienced writers can get tripped up when trying to write haiku. So, watch out for these common traps:

- Becoming a Syllable Counter, Not a Poet: This is when you’re so obsessed with 5-7-5 that you sacrifice meaning, imagery, or natural flow. If you have to twist a word awkwardly or add filler just for a syllable, it’s not working.

- Writing Mini-Essays: Trying to tell an entire story or explain a complex idea. Haiku is a snapshot, a moment, not a narrative arc.

- Over-Explaining Emotions: Stating “I felt sad” instead of describing the rain falling on a solitary windowpane. Let the images do the work of conveying the feeling.

- Lack of Sensory Detail: Using abstract words or vague descriptions (“nice weather,” “pretty flower”). Be specific and concrete.

- No Juxtaposition/Connection: Just stringing three observations together without creating a spark or deeper meaning between them. The lines should build upon each other, not just exist independently.

- Predictable or Clichéd Imagery: Relying on overused metaphors or descriptions. Find fresh ways to see and describe the ordinary.

- Ignoring the “Now”: Haiku often captures a specific, present moment. While memory can inspire, the poem itself should feel immediate.

Cultivating Your Haiku Practice

Mastery, as I’ve learned, is a journey, not a destination. Consistent practice and a curious mind are truly your greatest assets here.

- Read Haiku Extensively: Immerse yourself in the works of masters like Basho, Buson, Kobayashi Issa, and Masaoka Shiki. Also, make sure to explore contemporary English haiku poets. See how they achieve conciseness and clarity.

- Join a Haiku Community (Online or Local): Sharing your work and getting constructive feedback from others who really understand the form is incredibly valuable. Critiquing others’ work will also sharpen your own critical eye.

- Write Daily: Even if it’s just one haiku, make it a habit. The more you practice observing and distilling, the better you’ll become.

- Embrace Failure: Not every haiku you write will be a masterpiece. Some will simply be exercises. Learn from what doesn’t work, discard it, and move on.

- Broaden Your Observations: Don’t limit yourself to just nature themes. Urban landscapes, human interactions, fleeting thoughts – anything that sparks an unexpected image can be a subject.

Mastering the haiku is truly an exercise in meticulous observation, precise language, and profound distillation. It challenges you, the writer, to shed the superfluous and embrace the power of what’s essential. By sticking to its principles of conciseness and clarity, you not only craft seventeen impactful syllables but also cultivate a sharper eye, a more discerning mind, and a deeper appreciation for the beauty inherent in the world’s smallest moments. This ancient form, in its elegant restraint, offers a direct path to poetic potency, proving that often, less truly is more.