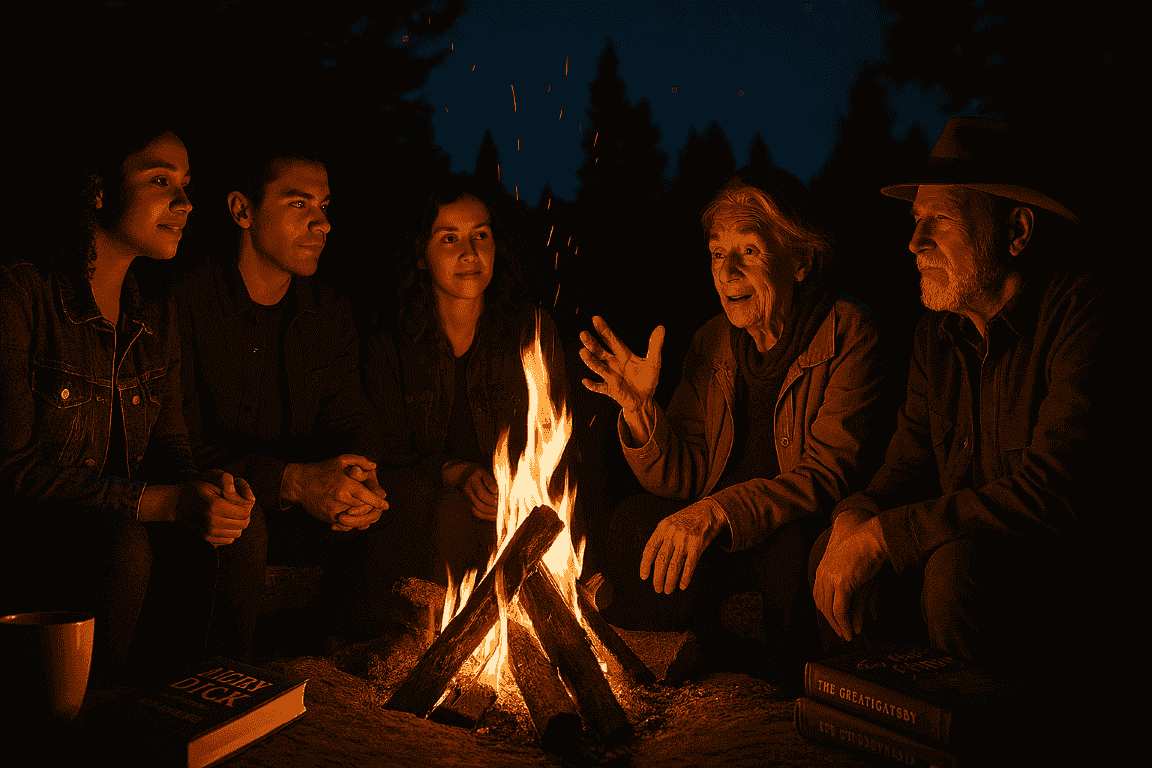

Storytelling is not merely an art; it is a fundamental human technology, a conduit for understanding, influence, and connection. From the ancient bards captivating tribal fires to the modern novelist shaping cultural discourse, master storytellers wield immense power. They don’t just recount events; they craft experiences, evoke emotions, and implant ideas that resonate long after the final word. This isn’t about mimicking their style, but dissecting their craft to elevate your own. This guide will provide a definitive, actionable framework for learning from these giants, bypassing superficial observation for deep, analytical engagement.

The Myth of Natural Talent: Deconstructing the Craft

Many believe master storytellers are born, not made. This is a comforting delusion that prevents genuine learning. While some possess innate charisma or an intuitive grasp of narrative, their mastery stems from relentless practice, meticulous observation, and a profound understanding of human psychology. Their “talent” is a finely honed skill set. To learn from them, we must abandon the notion of effortless genius and embrace the disciplined deconstruction of their work.

Phase 1: The Active Consumption – Beyond Passive Listening

Traditional advice suggests “reading widely.” This is a start, but insufficient. Passive consumption, where you simply absorb the narrative, yields little actionable insight. Active consumption transforms you from a spectator into an apprentice, dissecting the narrative in real-time.

1.1 The “Why” Question – Unearthing Intent

Every choice a storyteller makes, from a character’s stutter to a scene’s setting, is deliberate. Your task is to uncover the “why.”

- Example: When reading a Cormac McCarthy novel, don’t just accept the stark, unpunctuated prose. Ask: “Why does McCarthy absent himself from standard punctuation? What effect does this create on pace, tone, and character voice? How does it contribute to the desolate atmosphere?”

- Actionable Step: As you consume a story, pause frequently. For every striking element – a peculiar descriptor, a sudden plot twist, an unusual dialogue exchange – ask intensely: “Why this? What purpose does it serve? What emotional, thematic, or narrative function does it fulfill?” Jot down your hypotheses. Later, see if your initial thoughts align with the broader narrative impact.

1.2 Emotional Cartography – Mapping the Audience Journey

Master storytellers are emotional engineers. They don’t just tell you about feelings; they make you feel.

- Example: In a perfectly executed horror film, analyze not just when you jump, but how the storyteller builds to that moment. Is it the slow build of dread through unsettling sounds? The strategic use of shadows? The sudden silence before the crescendo of noise? What specific sensory details were employed to produce fear?

- Actionable Step: Create an “Emotional Arc Diagram” for the story. Plot the general emotional state of the audience throughout the narrative (e.g., curiosity, tension, amusement, despair, relief). For each pivot point, pinpoint the exact techniques used to shift your emotions. Was it a revelation, a character’s sacrifice, a sudden reversal of fortune? Catalog these triggers.

1.3 Structural Dissection – Identifying the Scaffolding

Beneath the glittering prose or compelling performance lies a robust skeletal structure. Master storytellers adhere to, subvert, or invent narrative structures with purpose.

- Example: Consider the classic “hero’s journey.” Instead of just recognizing it, trace each specific stage in a story like Star Wars: A New Hope. Where is the “Call to Adventure”? The “Refusal”? The “Meeting with the Mentor”? How does Lucas adapt or emphasize certain stages?

- Actionable Step: Break down the story into its fundamental parts: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution. But go deeper. Identify individual scenes or chapters and outline their purpose. Is this scene for character development? Plot advancement? World-building? How do these smaller building blocks contribute to the larger structure? Pay attention to pacing: where does the storyteller accelerate or decelerate the narrative flow, and why?

Phase 2: The Deep Dive – Microscopic Analysis

Once you’ve grasped the broader strokes, it’s time to zoom in. This phase focuses on the granular elements that, when combined, create narrative magic.

2.1 The Art of the Specific – Evoking Through Detail

Generic descriptions yield generic reactions. Master storytellers paint with specificity.

- Example: Instead of “The old house was scary,” a master might write, “The paint peeled like diseased skin from the gables, and one shutter, hanging precariously from a single rusted hinge, rattled a mournful dirge against the wind.” Notice the vivid, sensory details and the personification that elevates the description.

- Actionable Step: Isolate paragraphs or scenes where the storyteller uses description effectively. Copy them. Underline every concrete noun and active verb. Circle every sensory detail (sight, sound, smell, touch, taste). Analyze how these specific elements combine to create a powerful image or feeling. Attempt to rewrite a generic description you’ve read (or written) by injecting this level of specificity.

2.2 Dialogue Dynamics – Unmasking Character and Conflict

Dialogue is more than just characters talking. It reveals character, advances plot, and builds tension.

- Example: In a Quentin Tarantino film, listen to how characters speak. Their slang, their pauses, their verbal tics – all contribute to their identity and the film’s unique rhythm. Notice how conversations often simmer with unspoken tension or reveal hidden motives.

- Actionable Step: Select a compelling dialogue scene. Transcribe it. Then, analyze each line. What does it reveal about the speaker’s personality, background, or current emotional state? How does it move the plot forward or deepen conflict? Are there underlying power dynamics at play? Pay attention to subtext: what is not being said, but is clearly communicated between the lines?

2.3 Thematic Weaving – Subtlety of Meaning

Master storytellers don’t preach; they weave themes seamlessly into the narrative fabric.

- Example: The theme of redemption in Les Misérables isn’t stated outright. It’s explored through Jean Valjean’s agonizing choices, his persecution, and his eventual sacrifice. Every encounter, every challenge, subtly reinforces this overarching idea.

- Actionable Step: After consuming a story, identify what you believe are its central themes (e.g., love, loss, betrayal, identity, injustice). Go back through the narrative and pinpoint specific scenes, characters, or plot points that illustrate or explore these themes. How does the storyteller reinforce the theme without being didactic? How do different elements contribute to a unified thematic statement?

Phase 3: The Active Application – From Analysis to Creation

Knowledge without application is inert. This phase bridges the gap between understanding and doing.

3.1 The “Borrowing” Exercise – Strategic Imitation (Not Plagiarism)

This is not about stealing; it’s about internalizing techniques.

- Example: If you admire a storyteller’s use of suspense, identify a scene that achieves it. Then, using your own concept and characters, try to write a scene that employs the same techniques (e.g., withholding information, escalating stakes, using foreshadowing, focusing on sensory details that induce anxiety). The goal is to understand the mechanics, not to copy content.

- Actionable Step: Choose a specific technique you’ve analyzed (e.g., a specific type of opening hook, a method for revealing character, a way of building tension). Take one of your own existing story ideas or even an outline. Apply that chosen technique in a new scene or section. Don’t worry if it feels awkward at first; it’s a practice drill.

3.2 The “Rewrite” Challenge – Elevating Existing Narratives

Take a well-known, perhaps formulaic, story and attempt to elevate it using master storytelling principles.

- Example: Consider a simple fairy tale like “Little Red Riding Hood.” How would a master storyteller enhance the suspense? How would they deepen the grandmother’s character? What subtext might they introduce in the wolf’s dialogue? How would they make the woods feel truly menacing with specific, evocative detail?

- Actionable Step: Select a short, familiar narrative (a folk tale, a news story, or even one of your less developed ideas). Identify its weaknesses. Then, consciously apply 3-5 distinct principles you’ve learned from master storytellers (e.g., specific detail, emotional mapping, thematic depth, subtext in dialogue). Rewrite a key scene or the entire short narrative, focusing on elevating its impact and resonance.

3.3 The Feedback Loop – Externalizing Your Learning

You can only go so far in isolation. External feedback allows for blind spots to be revealed.

- Example: After applying a technique you learned, share your work. Instead of saying, “Is this good?” ask specific questions: “Does this scene evoke the intended sense of dread? Is the subtext palpable in this dialogue? Does this dialogue truly reveal Character X’s inner conflict?”

- Actionable Step: Find a trusted peer or a writing group. When seeking feedback on a piece where you’ve consciously applied certain techniques from master storytellers, specifically direct their attention to those areas. “I tried to build suspense by withholding information here, did it work for you? What did you feel?” This allows you to calibrate your understanding and application based on audience response.

The Continuous Journey: Storytelling as a Living Craft

Learning from master storytellers is not a one-time event; it’s a lifelong apprenticeship. The landscape of narrative evolves, and the masters of tomorrow are shaping their craft today. Embrace a mindset of perpetual curiosity and analytical rigor.

- Cultivate Deliberate Practice: Don’t just consume. Deconstruct. Don’t just write. Analyze, apply, and refine.

- Maintain a Storytelling Journal: Document your insights, your “why” questions, your structural analyses, and your application experiments. This creates a valuable personal library of narrative knowledge.

- Diversify Your Master Mentors: Don’t limit yourself to one genre or medium. Learn about pacing from a film director, character depth from a novelist, thematic resonance from a poet, and audience engagement from a stand-up comedian. Each offers unique insights into the broader art of narrative.

The pursuit of storytelling mastery is a noble one, for stories are the fabric of human experience. By diligently learning from those who have perfected the art, you equip yourself not just to tell tales, but to shape perceptions, ignite emotions, and leave an indelible mark on the hearts and minds of your audience. The power is not in imitation, but in understanding the underlying principles and weaving them into the unique tapestry of your own voice. Begin your journey today, not just as a reader or listener, but as an active, analytical apprentice dedicated to the profound art of narrative.